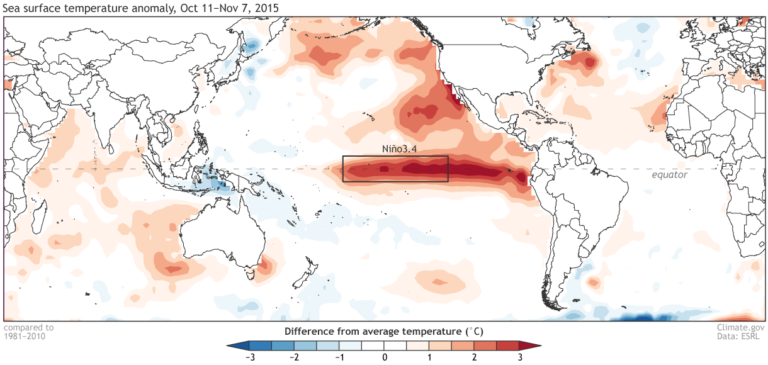

El Niño and Water Temperatures

I continue to run into good reads about El Niño, here is an explanation of the importance of changes in sea surface temperatures.

There are many variables that are monitored that let meteorologist know when we are in an El Niño phase. One of the most important is surface water temperatures in a region in the equatorial Pacific. The way it is measured is by taking the difference between the average temperature of the water and the current temperature, which is called an anomaly.

For example, if the average body temperature of 98.6ºF is used and your body temperature is 100ºF then the anomaly would be 1.4º. This meaning that your body is 1.4º above the average. This is somewhat how it is determine if we are under an El Niño phase.

When the water temperature is 0.5ºC warmer than the average for five consecutive 3-month periods, then it can officially be called an El Niño phase. The average difference between the temperatures during August-October this year was 1.7ºC, which is the second highest of the El Niño phases since 1950. To put this into perspective, since a 2ºC change does not sound like a lot, here is a calculation by Emily Becker from the Climate Prediction Center:

“In case you’re unimpressed by a 2°C (3.6°F) change, let’s do a little math. The area covered by the Niño3.4 region is a little more than 6 million square kilometers (2.4 million square miles). One cubic meter of water weighs 1,000 kg. So the top two meters (6.6 feet) of the Niño3.4 region contains about 12 quadrillion kilograms (about 13.6 trillion tons) of water.

The energy required to raise one kilogram of water one degree Celsius (the “specific heat”) is 4.19 kilojoules. A 2°C increase in just the top two meters of the Niño3.4 region adds up to an extra 100 quadrillion kilojoules (95 quadrillion BTUs), about equal to the annual energy consumption of the U.S.!”

So if you are wondering how warmer water temperatures in the Pacific Ocean affect us here in the United States, simply put, the atmosphere has to respond to 100 quadrillion kilojoules of energy, which is about how much energy the entire United States uses in one year.